Volume 16, Number 5—May 2010

Dispatch

Adenovirus 36 DNA in Adipose Tissue of Patient with Unusual Visceral Obesity

Abstract

Massive adipose tissue depositions in the abdomen and thorax sufficient to interfere with respiration developed in a patient with multiple medical problems. Biopsy of adipose tissue identified human adenovirus 36 (Adv 36) DNA. Adv 36 causes adipogenesis in animals and humans. Development of massive lipomatosis may be caused by Adv 36.

Infection with human adenovirus 36 (Adv 36) has been reported to cause a large accumulation of fat in 4 animals (chickens, mice, rats, and monkeys) (1–3). Selective deposition of visceral fat disproportional to total fat deposition was observed in some studies. The increase in visceral fat or total body fat in infected animals compared with uninfected animals was >100% in some experiments (1–3). Of animals that were infected, 60%–100% became obese compared with uninfected animals (1–4). Obesity was defined as a weight or fat content greater than the 85th percentile of the uninfected animals.

Several human studies have shown a correlation of antibodies to Adv 36 and obesity (4–8). In 1 study of >500 persons, 30% of obese persons and 11% of lean persons had antibodies to Adv 36 (4). The body weight of infected persons was ≈25 kg heavier than that of uninfected persons (4). In 26 pairs of twins with discordant Adv 36 antibody status, infected twins were heavier and fatter (4). In a group of obese school children from South Korea, 30% had antibodies to Adv 36, and infected children had higher body mass index z-scores than uninfected children (5). However, in animals and adults in the United States, serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels were paradoxically reduced, despite the obesity (1–4). Recent reports of adults in Italy and children in South Korea support the association of Adv 36 and obesity, and show that Adv 36 is more common in obese persons; prevalence ranges from 29% to 65% (6,7).

The mechanisms responsible for the increased adiposity are changes in gene expression of multiple enzymes and transcription factors by the virus (8–15). In adipocytes, the sterol regulatory element binding protein pathway is increased, resulting in increases in levels of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 and fatty acid synthase. Because levels of transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-β, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and lipoprotein lipase are also increased, lipid transport into cells and fatty acid synthesis within cells is increased (8–15). In muscle cells, gene expression of glucose transporters Glut 1 and Glut 4 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase is increased, which results in noninsulin-mediated increases in glucose transport (14).

These changes are thought to be caused by the action of the Adv 36 open reading frame 1 early region 4 gene and may be blocked by small interfering RNA or the antiviral drug cidofovir (11,13). When the open reading frame 1 early region 4 gene was transferred to a retrovirus and inserted into preadipocytes in vitro, the gene was capable of inducing the enzymes and enhancing fat accumulation (13).

Adv 36 DNA persists in multiple tissues of infected animals for long periods after initial infection (3). Viral DNA was isolated from brain, lung, liver, muscle, and adipose tissue of monkeys 7 months after initial infection, long after the active virus has disappeared from blood and feces (3). The virus DNA apparently continues to alter gene expression chronically in tissues.

We report a patient with massive fat deposits in the thorax and abdomen. We postulate that these abnormal adipose tissue deposits were caused by Adv 36 infection.

The patient, a 62-year old man who was diagnosed with high-grade large cell lymphoma in 1999, received multidrug (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) chemotherapy, central nervous system prophylaxis with cytarabine, and high-dose methotrexate. In February 2000, he underwent autologous bone marrow transplantation and received a conditioning regimen of etoposide, cytoxan, and fractionated total-body irradiation. Hypothyroidism, chemoradiation-induced hypogonadism, and adrenal insufficiency developed in the patient, which required chronic glucocorticoid replacement.

During the next 7 years, prostate cancer, rectal ulcer necessitating colon diversion, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus developed in the patient; he was treated with insulin for the diabetes. He was hospitalized for respiratory insufficiency in August, 2007, which was thought to be caused or exacerbated by massive intrathoracic and intraabdominal fat deposits. He had obesity of his neck, lateral chest, and abdomen, but limited subcutaneous fat in his abdomen and upper extremities. He had no buffalo hump, round facies, or other signs of Cushing syndrome. The patient had tachycardia with muffled heart sounds, dullness in the base of the right chest, and bibasilar diminished breath sounds. A computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen showed fatty densities extending into the intrabdominal, intraperitoneal, and retroperitoneal areas and herniating through the esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum (Figure 1). These fatty densities extended within the pericardium without definite pericardial effusion.

The patient’s weight was 113 kg, height 183 cm, body mass index 34, waist circumference 145 cm, and hip circumference 111 cm. Laboratory tests showed triglycerides 1.356 mmol/L, total cholesterol 2.2015 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 0.5957 mmol/L, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol 0.9842 mmol/L. The serum lipids values represent marked decreases from previous measurements. In December 2002, his low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level was 2.7412 mmol/L. In April 2007, his serum triglyceride level was 4.92244 mmol/L. The result of a test for serum immunoglobulin (Ig) M against adenoviruses was negative (0.07 IU), and the result of a test for serum IgG was positive (2.18 IU).

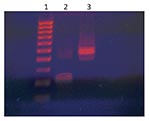

Infection with Adv 36 causing disseminated lipomatosis was suspected. A subcutaneous fat biopsy specimen was assayed for Adv 36 DNA by nested PCR (4). Three of 4 adipose tissue samples showed a band compatible with Adv 36 DNA. Water controls in the assay had negative results. A HaeIII digest of the presumed Adv 36 DNA band showed digestion at the expected site and yielded 2 bands of equal size (Figure 2). Sequencing of the DNA band by the Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center Molecular Biology Core (Richmond, VA, USA) identified the sequence as Adv 36 DNA.

As a control, samples of adipose tissue obtained by needle fat biopsy from 12 obese persons without abnormal adipose tissue deposits were evaluated by nested PCR and quantitative PCR by using proprietary Taqman primers and probe (Obetech, Richmond, VA, USA). These persons provided written informed consent. Samples for quantitative PCR were analyzed with an ABI Step One PCR apparatus (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Two of the 8 samples assayed by nested PCR were positive and 5 of 12 samples assayed by quantitative PCR were positive. The prevalence of Adv 36 infection identified by PCR was similar to that identified by serum neutralization in obese adults in the United States (5).

Adv 36 DNA in the adipose tissue of this patient documents that he was infected with this virus. The propensity of Adv 36 to increase visceral adipose tissue in experimentally infected animals suggests that the abnormal adipose tissue deposits within the abdomen and chest cavities and in the subcutaneous spaces of the chest and neck could be caused by Adv 36 infection. He was being treated with replacement corticosteroids but did not have signs of Cushing syndrome.

More research is needed to determine if Adv 36 plays a role in abnormal adipose tissue deposits/lipomatosis. If Adv 36 is found to be a cause, research is needed to identify effective antiviral agents with a more tolerable side effect profile. Cidofovir is effective against Adv 36 in vitro, but has major side effects in humans.

Dr Salehian is an associate clinical professor of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism in the Department of Diabetes at the City of Hope and Beckman Research Institute, Duarte, California. His primary research interests are glucocorticoid myopathy, thyroid cancer, metabolism and nutrition in patients with critical illnesses, and cachexia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Ward for performing the PCR assays and Ellen Anderson for assistance with collecting the control samples.

This study was supported by the City of Hope and Beckman Research Institute and the Obetech Obesity Research Center.

References

- Dhurandhar NV, Israel BA, Kolesar JM, Mayhew GF, Cook ME, Atkinson RL. Increased adiposity in animals due to a human virus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:989–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dhurandhar NV, Israel BA, Kolesar JM, Mayhew G, Cook ME, Atkinson RL. Transmissibility of adenovirus induced adiposity in a chicken model. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:990–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dhurandhar NV, Whigham LD, Abbott DH, Schultz-Darken NJ, Israel BA, Bradley SM, Human adenovirus Ad-36 promotes weight gain in male rhesus and marmoset monkeys. J Nutr. 2002;132:3155–60.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Atkinson RL, Dhurandhar NV, Allison DB, Bowen RL, Israel BA, Albu JB, Human adenovirus-36 is associated with increased body weight and paradoxical reduction of serum lipids. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29:281–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Atkinson RL, Lee I, Shin HJ, He J. Human adenovirus-36 antibody status is associated with obesity in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;10:1–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Trovato GM, Castro A, Tonzuso A, Garozzo A, Martines GF, Pirri C, Human obesity relationship with Ad36 adenovirus and insulin resistance. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:1402–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Na HN, Hong YM, Kim J, Kim HK, Jo I, Nam JH. Association between human adenovirus-36 and lipid disorders in Korean schoolchildren. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34:89–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vangipuram SD, Sheele J, Atkinson RL, Holland TC, Dhurandhar NV. A human adenovirus enhances preadipocyte differentiation. Obes Res. 2004;12:770–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vangipuram SD, Yu M, Tian J, Stanhope KL, Pasarica M, Havel PJ, Adipogenic human adenovirus-36 reduces leptin expression and secretion and increases glucose uptake by fat cells. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:87–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pasarica M, Shin AC, Yu M, Ou Yang HM, Rathod M, Jen KL, Human adenovirus 36 induces adiposity, increases insulin sensitivity, and alters hypothalamic monoamines in rats. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1905–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rathod M, Vangipuram SD, Krishnan B, Heydari AR, Holland TC, Dhurandhar NV. Viral mRNA expression but not DNA replication is required for lipogenic effect of human adenovirus Ad-36 in preadipocytes. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:78–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pasarica M, Mashtalir N, McAllister EJ, Kilroy GE, Koska J, Permana P, Adipogenic human adenovirus Ad-36 induces commitment, differentiation, and lipid accumulation in human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:969–78. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rogers PM, Fusinski KA, Rathod MA, Loiler SA, Pasarica M, Shaw MK, Human adenovirus Ad-36 induces adipogenesis via its E4 orf-1 gene. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:397–406. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang ZQ, Cefalu WT, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Qin J, Son L, Human adenovirus type 36 enhances glucose uptake in diabetic and nondiabetic human skeletal muscle cells independent of insulin signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57:1805–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rogers PM, Mashtalir N, Rathod MA, Dubuisson O, Wang Z, Dasuri K, Metabolically favorable remodeling of human adipose tissue by human adenovirus type 36. Diabetes. 2008;57:2321–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 16, Number 5—May 2010

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Richard L. Atkinson, Obetech Obesity Research Center, 800 East Leigh St, Richmond, VA 23219, USA

Top