Volume 18, Number 1—January 2012

Dispatch

Molecular Evolution of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Gene, Canada, 2006–2010

Figure

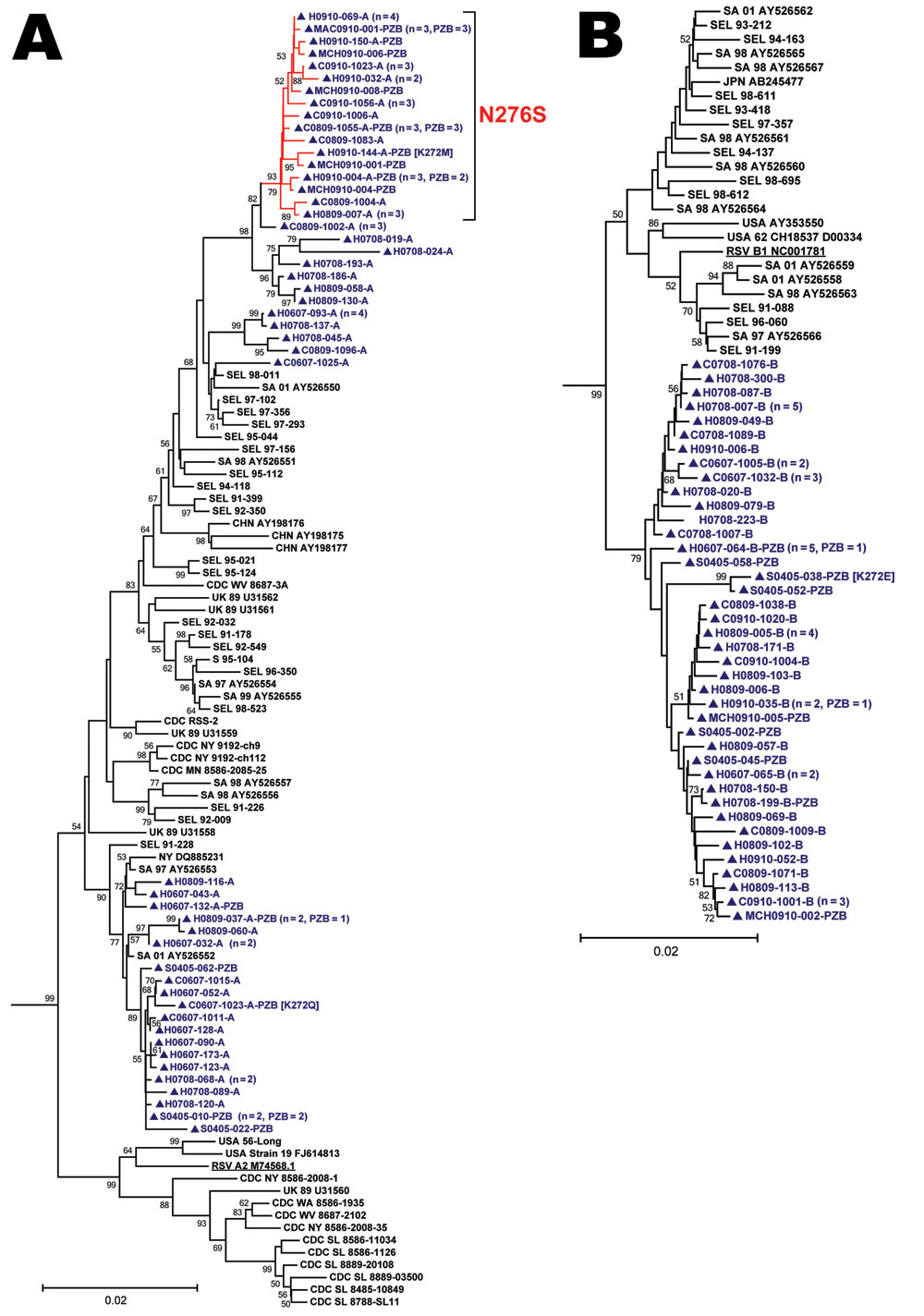

Figure. Phylogenetic analysis of 170 near–full-length unique respiratory syncitial virus fusion (RSV-F) gene sequences (nt 79–1602). Panels A and B are detailed phylograms of the RSV-A and RSV-B taxa analyzed, respectively. One bovine RSV-F sequence was added to the dataset (GenBank accession no. AF295543.1) as the outgroup (not shown) and used for rooting the phylograms. Topology was inferred by using the neighbor-joining method, and evolutionary distances were computed by using the maximum-composite likelihood method in MEGA5 software (www.megasoftware.net). The topologic accuracy of the tree was evaluated by using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Only bootstrap values >50% are shown. Blue text and triangles represent RSV strains isolated in Canada and sequenced at the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec; red branches indicates a sublineage of RSV-A with a N276S mutation; underlining indicates prototypical RSV A2 and RSV B1 strains. The clinical origin of strains from Canada (prospective study hospitalized patient [H] or clinic patient [C]; 2004–2005 palivizumab study patient [S]; retrospectively identified patient from the Montréal Children’s Hospital [MCH] or McMaster Children’s Hospital [MAC]) is indicated, followed by the year collected, the specimen identifier, and the result of RSV genogroup testing (RSV-A [A], RSV-B [B]) by multiplex PCR/DNA hybridization assay (14). Specimens with a nonsilent mutation at codon 272 have the amino acid substitution identified in brackets. When a taxon represents >1 identical sequences, the number of patients that it represents and the number of palivizumab recipients (PZB) among these patients are noted in parentheses. SA, South Africa; CHN, People’s Republic of China; UK, United Kingdom, JPN, Japan; AUS, Australia; USA, United States; CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NY, New York; SL, St. Louis; WV, West Virginia; MN, Minnesota; MD, Maryland; WA, Washington; SEL, Seoul, South Korea. Scale bars represent substitutions per basepair per the indicated horizontal distance.

References

- Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Welliver RC. Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. J Pediatr. 2003;143:S112–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Collins PL, Crowe JE. Respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Field’s virology.,5th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. p. 1601–46.

- Crowe JE, Firestone CY, Crim R, Beeler JA, Coelingh KL, Barbas CF, Monoclonal antibody-resistant mutants selected with a respiratory syncytial virus–neutralizing human antibody fab fragment (Fab 19) define a unique epitope on the fusion (F) glycoprotein. Virology. 1998;252:373–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huang K, Incognito L, Cheng X, Ulbrandt ND, Wu H. Respiratory syncytial virus–neutralizing monoclonal antibodies motavizumab and palivizumab inhibit fusion. J Virol. 2010;84:8132–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: policy statements–modified recommendations for use of palivizumab for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1694–701. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhao X, Chen FP, Megaw AG, Sullender WM. Variable resistance to palivizumab in cotton rats by respiratory syncytial virus mutants. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1941–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Adams O, Bonzel L, Kovacevic A, Mayatepek E, Hoehn T, Vogel M. Palivizumab-resistant human respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:185–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhu Q, McAuliffe JM, Patel NK, Palmer-Hill FJ, Yang CF, Liang B, Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus preclinical and clinical variants resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies palivizumab and/or motavizumab. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:674–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kim YK, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Genetic variability of the fusion protein and circulation patterns of genotypes of the respiratory syncytial virus. J Med Virol. 2007;79:820–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zheng H, Storch GA, Zang C, Peret TC, Park CS, Anderson LJ. Genetic variability in envelope-associated protein genes of closely related group A strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Virus Res. 1999;59:89–99. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gilca R, De Serres G, Tremblay M, Vachon ML, Leblanc E, Bergeron MG, Distribution and clinical impact of human respiratory syncytial virus genotypes in hospitalized children over 2 winter seasons. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:54–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Peret TC, Hall CB, Hammond GW, Piedra PA, Storch GA, Sullender WM, Circulation patterns of group A and B human respiratory syncytial virus genotypes in 5 communities in North America. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1891–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Raymond F, Carbonneau J, Boucher N, Robitaille L, Boisvert S, Wu WK, Comparison of automated microarray detection with real-time PCR assays for detection of respiratory viruses in specimens obtained from children. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:743–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Boivin G, Caouette G, Frenette L, Carbonneau J, Ouakki M, De Serres G. Human respiratory syncytial virus and other viral infections in infants receiving palivizumab. J Clin Virol. 2008;42:52–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar