Volume 27, Number 2—February 2021

Research

Plasmodium falciparum Histidine-Rich Protein 2 and 3 Gene Deletions in Strains from Nigeria, Sudan, and South Sudan

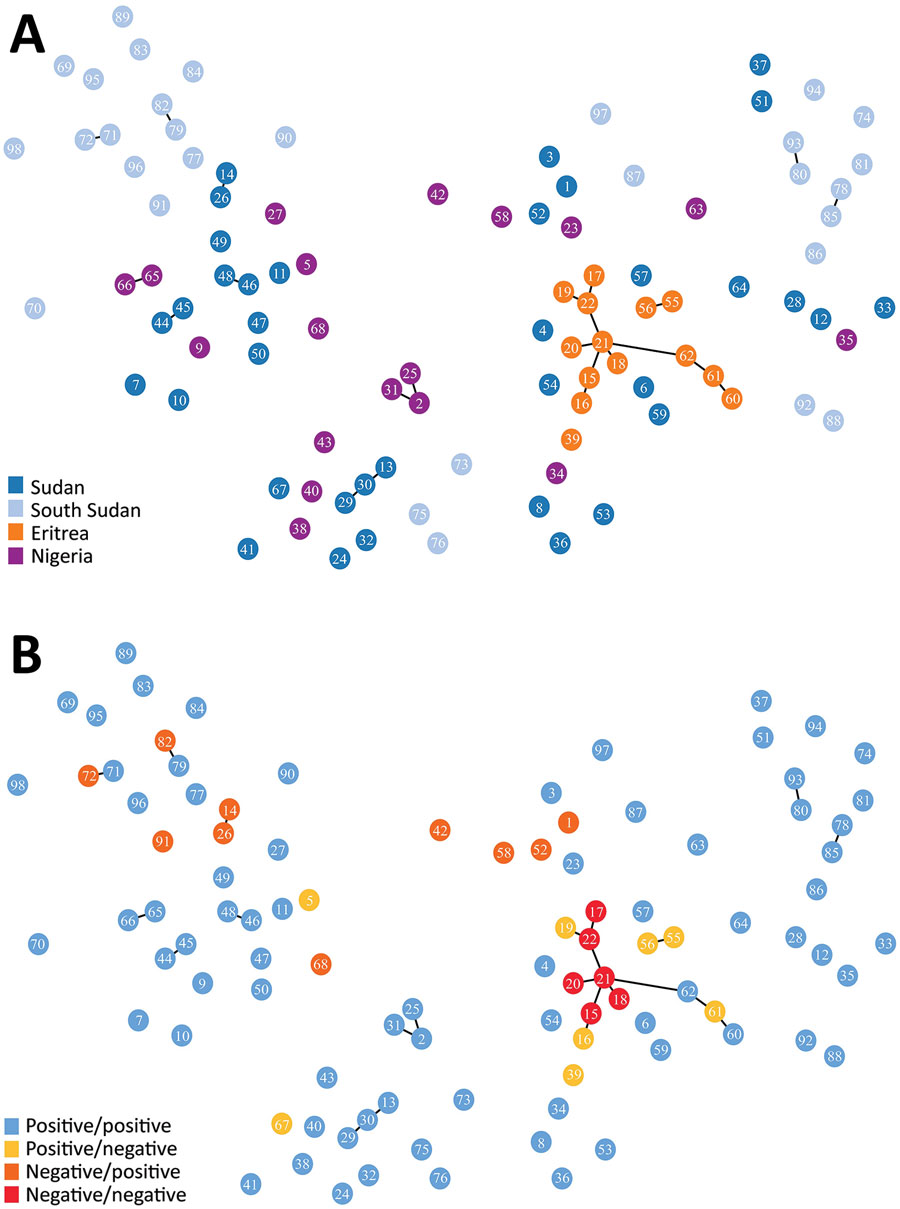

Figure 2

Figure 2. Minimum spanning tree of microsatellite allelic data showing genetic relatedness of Plasmodium falciparum populations from Sudan, South Sudan, Nigeria, and Eritrea (A), and pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 deletion status of haplotypes (B) (positive: gene present; negative: gene absent). Numbered circles represent specific haplotypes. Plots were generated using PHYLOViZ software (25) with a cutoff value of 2 (minimum differences for 2 microsatellite loci) depicted as lines connecting haplotypes and a cutoff value of 3 depicted as haplotype circle arrangements/proximities.

References

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2015. Geneva: The Organization; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Strategy for malaria elimination in the Greater Mekong Subregion: 2015–2030. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2015.

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2019. Geneva: The Organization; 2019.

- Batwala V, Magnussen P, Hansen KS, Nuwaha F. Cost-effectiveness of malaria microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests versus presumptive diagnosis: implications for malaria control in Uganda. Malar J. 2011;10:372. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Australian Government Department of Health. Malaria laboratory case definition (LCD) 2018 [updated 2019 Jan 2] [cited 2019 Sep 15]. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-phlncd-malaria.htm

- Jimenez A, Rees-Channer RR, Perera R, Gamboa D, Chiodini PL, Gonzalez IJ, et al. Analytical sensitivity of current best-in-class malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2017;16:128. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Das S, Peck RB, Barney R, Jang IK, Kahn M, Zhu M, et al. Performance of an ultra-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum HRP2-based rapid diagnostic test with recombinant HRP2, culture parasites, and archived whole blood samples. Malar J. 2018;17:118. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Donald W, Pasay C, Guintran J-O, Iata H, Anderson K, Nausien J, et al. The utility of malaria rapid diagnostic tests as a tool in enhanced surveillance for malaria elimination in Vanuatu. PLoS One. 2016;11:

e0167136 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Parr JB, Verity R, Doctor SM, Janko M, Carey-Ewend K, Turman BJ, et al. Pfhrp2-deleted Plasmodium falciparum parasites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a national cross-sectional survey. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:36–44. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Berhane A, Anderson K, Mihreteab S, Gresty K, Rogier E, Mohamed S, et al. Major threat to malaria control programs by Plasmodium falciparum lacking histidine-rich protein 2, Eritrea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:462–70. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Amoah LE, Abankwa J, Oppong A. Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein-2 diversity and the implications for PfHRP 2: based malaria rapid diagnostic tests in Ghana. Malar J. 2016;15:101. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Beshir KB, Sepulveda N, Bharmal J, Robinson A, Mwanguzi J, Busula AO, et al. Plasmodium falciparum parasites with histidine-rich protein 2 (pfhrp2) and pfhrp3 gene deletions in two endemic regions of Kenya. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14718. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Kozycki CT, Umulisa N, Rulisa S, Mwikarago EI, Musabyimana JP, Habimana JP, et al. False-negative malaria rapid diagnostic tests in Rwanda: impact of Plasmodium falciparum isolates lacking hrp2 and declining malaria transmission. Malar J. 2017;16:123. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Funwei R, Nderu D, Nguetse CN, Thomas BN, Falade CO, Velavan TP, et al. Molecular surveillance of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 genes deletion in Plasmodium falciparum isolates and the implications for rapid diagnostic tests in Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2019;196:121–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Agaba BB, Yeka A, Nsobya S, Arinaitwe E, Nankabirwa J, Opigo J, et al. Systematic review of the status of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletion, approaches and methods used for its estimation and reporting in Plasmodium falciparum populations in Africa: review of published studies 2010–2019. Malar J. 2019;18:355. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Bharti PK, Chandel HS, Ahmad A, Krishna S, Udhayakumar V, Singh N. Prevalence of pfhrp2 and/or pfhrp3 gene deletion in Plasmodium falciparum population in eight highly endemic states in India. PLoS One. 2016;11:

e0157949 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Li P, Xing H, Zhao Z, Yang Z, Cao Y, Li W, et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 in the China-Myanmar border area. Acta Tropica. 2015;152:26–31. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Akinyi S, Hayden T, Gamboa D, Torres K, Bendezu J, Abdallah JF, et al. Multiple genetic origins of histidine-rich protein 2 gene deletion in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Peru. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2797. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gendrot M, Fawaz R, Dormoi J, Madamet M, Pradines B. Genetic diversity and deletion of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 and 3: a threat to diagnosis of P. falciparum malaria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:580–5. DOIGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. False-negative RDT results and implications of new reports of P. falciparum histidine-rich protein 2/3 gene deletions. WHO reference no. WHO/HTM/GMP/2017.18. Geneva: The Organization; 2017.

- World Health Organization, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance. Results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 7 (2015–2016). Geneva: The Organization; 2017.

- Padley D, Moody AH, Chiodini PL, Saldanha J. Use of a rapid, single-round, multiplex PCR to detect malarial parasites and identify the species present. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:131–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cheng Q, Gatton ML, Barnwell J, Chiodini P, McCarthy J, Bell D, et al. Plasmodium falciparum parasites lacking histidine-rich protein 2 and 3: a review and recommendations for accurate reporting. Malar J. 2014;13:283. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Anderson TJ, Haubold B, Williams JT, Estrada-Franco JG, Richardson L, Mollinedo R, et al. Microsatellite markers reveal a spectrum of population structures in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1467–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ribeiro-Goncalves B, Francisco AP, Vaz C, Ramirez M, Carrico JA. PHYLOViZ Online: web-based tool for visualization, phylogenetic inference, analysis and sharing of minimum spanning trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W246–51. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Goudet J. FSTAT (version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered. 1995;86:485–6. DOIGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2017. Geneva: The Organization; 2017.

- Boyce MR, O’Meara WP. Use of malaria RDTs in various health contexts across sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:470. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Altaras R, Nuwa A, Agaba B, Streat E, Tibenderana JK, Strachan CE. Why do health workers give anti-malarials to patients with negative rapid test results? A qualitative study at rural health facilities in western Uganda. Malar J. 2016;15:23. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Baker J, McCarthy J, Gatton M, Kyle DE, Belizario V, Luchavez J, et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (PfHRP2) and its effect on the performance of PfHRP2-based rapid diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:870–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gatton ML, Dunn J, Chaudhry A, Ciketic S, Cunningham J, Cheng Q. Implications of parasites lacking Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 on malaria morbidity and control when rapid diagnostic tests are used for diagnosis. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1156–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Neumann K, Hermans F. What drives human migration in Sahelian countries? A meta-analysis. Popul Space Place. 2017;23:

e1962 . DOIGoogle Scholar - Quakyi IA, Adjei GO, Sullivan DJ, Jr., Laar A, Stephens JK, Owusu R, et al. Diagnostic capacity, and predictive values of rapid diagnostic tests for accurate diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum in febrile children in Asante-Akim, Ghana. Malar J. 2018;17:468. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Hagen RM, Hinz R, Tannich E, Frickmann H. Comparison of two real-time PCR assays for the detection of malaria parasites from hemolytic blood samples - Short communication. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp). 2015;5:159–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Abakar MF, Schelling E, Béchir M, Ngandolo BN, Pfister K, Alfaroukh IO, et al. Trends in health surveillance and joint service delivery for pastoralists in West and Central Africa. Rev Sci Tech. 2016;35:683–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Evidence review group on border malaria: meeting report. World Health Organization, 2018 Malaria Policy Advisory Committee Meeting, October 17–19, 2018. Report no. WHO/CDS/GMP/MPAC/2018.13. Geneva: The Organization; 2018.

- Watson OJ, Verity R, Ghani AC, Garske T, Cunningham J, Tshefu A, et al. Impact of seasonal variations in Plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission on the surveillance of pfhrp2 gene deletions. eLife. 2019;8:

e40339 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: December 22, 2020

Page updated: January 23, 2021

Page reviewed: January 23, 2021

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.