Volume 31, Number 3—March 2025

Dispatch

Mycobacterium ulcerans in Possum Feces before Emergence in Humans, Australia

Figure 2

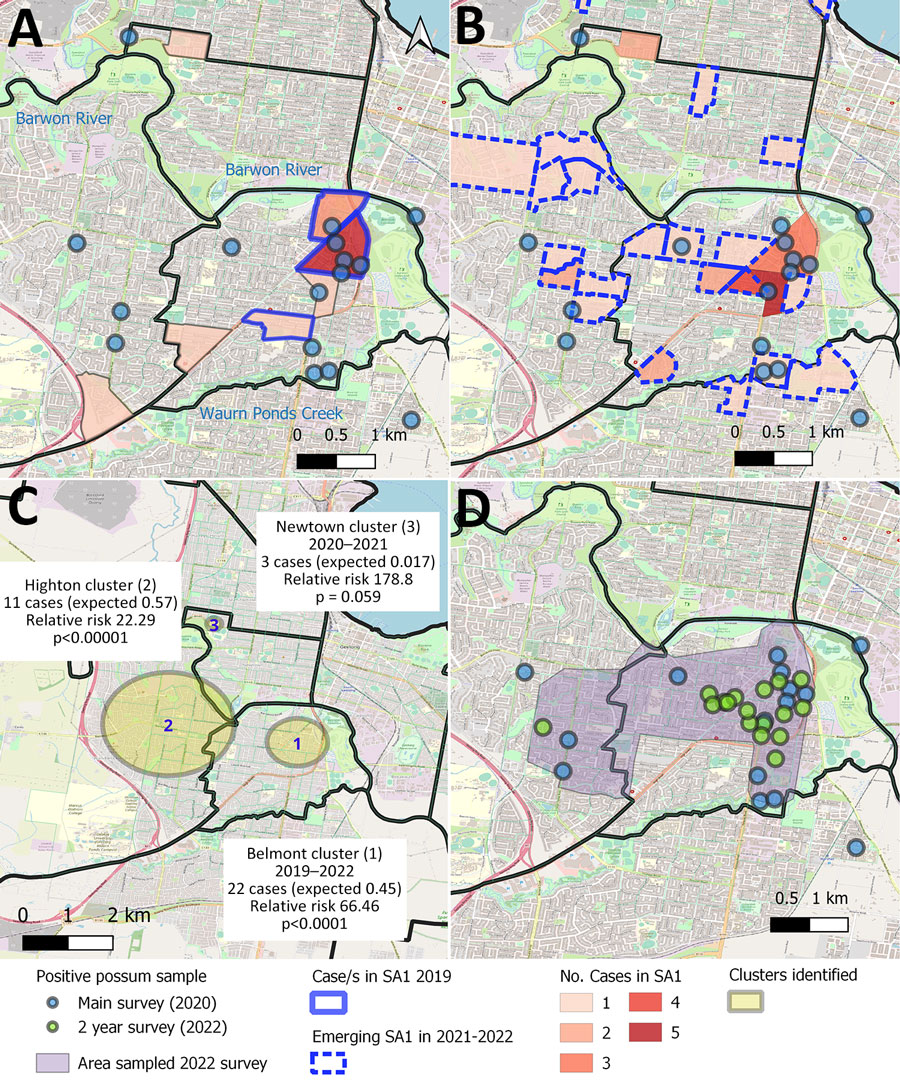

Figure 2. Distribution, clustering, and timing of Buruli ulcer cases in relation to Mycobacterium ulcerans–positive possum fecal samples, Victoria, Australia. A) Number and home location of human Buruli ulcer cases in Statistical Area SA1 in 2019–2020, compared with the distribution of M. ulcerans–positive possum fecal samples collected in the systematic main survey in 2020. Solid blue outline indicates areas in 2019 in which cases were tightly clustered during 2019; colored areas without borders had cases in 2020 only, B) Number and home location of human Buruli ulcer cases in Statistical Area SA1 in 2021–2022, compared with the distribution of M. ulcerans–positive possum fecal samples collected in the systematic main survey in 2020. Dashed blue outline indicates areas with cases only in 2021–2022 and not 2019–2020. Blue circles indicate 100-meter radius around the collection location. C) Spatiotemporal clustering of human Buruli ulcer cases from 2011–2022 in Geelong suburbs, Australia. The observed number of cases within each cluster are compared to the expected number for the estimated resident population of the area during the period (3), under the null hypothesis (no spatiotemporal clustering). D) Changing distribution of positive possum fecal samples from 2020 (blue) and 2022 (green).

References

- World Health Organization. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: first WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: The Organization; 2010.

- Merritt RW, Walker ED, Small PL, Wallace JR, Johnson PD, Benbow ME, et al. Ecology and transmission of Buruli ulcer disease: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:

e911 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - O’Brien DP, Jeanne I, Blasdell K, Avumegah M, Athan E. The changing epidemiology worldwide of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;147:

e19 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Loftus MJ, Tay EL, Globan M, Lavender CJ, Crouch SR, Johnson PDR, et al. Epidemiology of Buruli ulcer infections, Victoria, Australia, 2011–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1988–97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Buultjens AH, Vandelannoote K, Meehan CJ, Eddyani M, de Jong BC, Fyfe JAM, et al. Comparative genomics shows that Mycobacterium ulcerans migration and expansion preceded the rise of Buruli ulcer in southeastern Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02612–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mee PT, Buultjens AH, Oliver J, Brown K, Crowder JC, Porter JL, et al. Mosquitoes provide a transmission route between possums and humans for Buruli ulcer in southeastern Australia. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9:377–89. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McNamara BJ, Blasdell KR, Yerramilli A, Smith IL, Clayton SL, Dunn M, et al. Comprehensive case-control study of protective and risk factors for Buruli ulcer, southeastern Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:2032–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fyfe JA, Lavender CJ, Handasyde KA, Legione AR, O’Brien CR, Stinear TP, et al. A major role for mammals in the ecology of Mycobacterium ulcerans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:

e791 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Blasdell KR, McNamara B, O’Brien DP, Tachedjian M, Boyd V, Dunn M, et al. Environmental risk factors associated with the presence of Mycobacterium ulcerans in Victoria, Australia. PLoS One. 2022;17:

e0274627 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Vandelannoote K, Buultjens AH, Porter JL, Velink A, Wallace JR, Blasdell KR, et al. Statistical modeling based on structured surveys of Australian native possum excreta harboring Mycobacterium ulcerans predicts Buruli ulcer occurrence in humans. eLife. 2023;12:

e84983 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Australian Bureau of Statistics. Regional population, estimated residential population 2001–2020. Canberra: The Bureau; 2022.

- Blasdell KR, McNamara B, O’Brien DP, Tachedjian M, Boyd V, Dunn M, et al. Environmental risk factors associated with the presence of Mycobacterium ulcerans in Victoria, Australia. PLoS One. 2022;17:

e0274627 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Department of Health Victoria. Local public health units. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 5]. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/local-public-health-units

- Coutts SP, Lau CL, Field EJ, Loftus MJ, Tay EL. Delays in patient presentation and diagnosis for Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection) in Victoria, Australia, 2011–2017. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4:100. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar