Volume 17, Number 12—December 2011

Dispatch

High Prevalence of Human Liver Infection by Amphimerus spp. Flukes, Ecuador

Abstract

Amphimerus spp. flukes are known to infect mammals, but human infections have not been confirmed. Microscopy of fecal samples from 397 persons from Ecuador revealed Opisthorchiidae eggs in 71 (24%) persons. Light microscopy of adult worms and scanning electron microscopy of eggs were compatible with descriptions of Amphimerus spp. This pathogen was only observed in communities that consumed undercooked fish.

The genus Amphimerus Barker 1911 infects mammals from the Americas, including Canada, the United States, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Brazil, and Peru. Eleven species are reported (1–7). In Ecuador, a trematode resembling Amphimerus spp. but identified as Opisthorchis guayaquilensis has been reported (8,9).

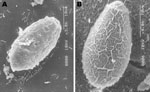

Amphimerus spp. are parasitic liver flukes in the bile ducts of mammals, birds, and reptiles (1). Although these digenetic trematodes of the Opisthorchiidae family are closely related to the genera Clonorchis and Opisthorchis, there are morphologic differences. The vitellaria in adult Amphimerus spp. trematodes are distributed in 4 groups, 2 anterior and 2 posterior; the latter groups extend beyond the posterior testis; the ventral sucker is larger than the oral, and the testes are rounded or slightly lobulated. In contrast, the vitellaria in Clonorchis and Opisthorchis spp. worms exist only in front of the testes. Additionally, Clonorchis spp. trematodes have 2 large highly branched testes; testes in Opisthorchis spp. trematodes are always lobulated (1,2). The eggs of the flukes from these genera can be differentiated only by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Definitive diagnosis using light microscopy of the flukes of the Opisthorchiidae family, therefore, is not possible unless the adult worm is collected and identified. Through isolation of adult worms and SEM of eggs, we found a high prevalence of human infection with a trematode of the genus Amphimerus in Ecuador.

In June 2009, during a routine fecal examination for the parent study, 4 samples tested positive for eggs of the Opisthorchiidae family in 3 indigenous Chachi communities along the Cayapas River in the northern coastal rainforest of Ecuador. In January 2010, a follow-up survey was conducted in the same 3 communities (total population 589); all villagers, whether symptomatic or not, were asked to provide a fecal sample. Specifically, a community meeting was held in each village, study objectives were explained, and villagers were asked for their voluntary participation. Flasks were distributed to all villagers and collected the next day in the school and by going house to house. The Chachis, the predominant group in these 3 communities, represent 13% of the 24,000 inhabitants in the region. Afro-Ecuadorians and mestizos also reside in this region (10,11).

A total of 297 (50.4%) community members 3–77 years of age provided samples. To each person providing a sample, a questionnaire was administered regarding types of food eaten and cooking practices. Samples were preserved in 10% formalin, transported to a laboratory in Quito, and stored at 4°C until examination by light microscopy. Eggs were concentrated by using the formalin-ether technique. In addition, 120 fecal samples from Afro-Ecuadorian and mestizo persons were examined. The villagers were informed of the study in their local Chapalache language by community health community workers. The ethical committee of the Central University approved this study.

Duodendoscopy was performed in 4 patients by a gastroenterology specialist to examine the biliary liquid; the microscopy of this liquid showed eggs identical to those found in their feces. These patients received praziquantel (75 mg/kg in 3 doses/3 d), and were purged with 10 mg of bisacodilo. Fecal samples were collected and examined for worms as previously described (12). Recovered worms were fixed with 10% formalin, stained with Diff-Quik fixative (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), and identified by comparing their morphologic features to known adult Clonorchis and Opisthorchis spp. worms. Community health workers collected and examined the livers of 3 cats and 3 dogs from 1 of the 3 communities. All 6 livers had eggs and high numbers of adult parasites in the bile ducts. Adult parasites were stained, and microscopic studies showed them to be identical to those in the human specimens.

A total of 71 (24%) of the 297 fecal samples from the indigenous Chachi were positive for Opisthorchiidae eggs (Table). In contrast all 120 samples from Afro-Ecuadorian and mestizo persons were negative. Eggs were yellow-brown and measured 28–33 μm ×12–15 μm (n = 20). The operculum and the shoulders, however, were not prominent as they are in Clonorchis and Opisthorchis eggs. Occasionally, a small knob, but most frequently a curved spine, was seen on the abopercular end. Although, by light microscopy, the shape and size of the eggs resembled that of the other liver flukes, the patterns of the eggshell surface were distinct when viewed with SEM (Figure 1). This observation is corroborated with published photographs (3).

After participants were treated with praziquantel, a total of 8 worms were recovered from 4 human participants and dozens from cat and dog livers; all were placed in saline. The worms were delicate, leaf-shaped, elongated, and red-pink and measured 8–13.6 mm long (average 10.2 mm) × 0.5–1.1 mm wide (n = 15). After a few minutes, the worms coiled in an S shape and became transparent or whitish. Once stained, the following features were observed: 1) the vitellaria divided into an anterior and posterior group with the posterior group extending the level of the posterior testis; 2) a ventral sucker larger than oral sucker; and 3) 2 rounded testes (Figure 2). On the basis of these morphologic characteristics of the adults and the SEM findings of the eggs, the parasite was identified as Amphimerus spp.

Our study demonstrates that the liver fluke of the genus Amphimerus can infect humans. We found a high prevalence (15.5%–34.1%) of infection with Amphimerus spp. trematodes in the surveyed communities (Table). Samples from the Afro-Ecuadorian and mestizo population were all negative for Opisthorchiidae eggs. Amphimerus spp. trematodes are believed to be transmitted, as are the other members of the Opisthorchiidae family, by ingestion of raw or undercooked fish (2). In our survey, most Chachis reported eating smoked fish caught in the rivers. Food sharing is more common among Chachi than Afro-Ecuadorians and mestizo families (13). Notably, the most remote village (120 km inland from the coast) had the highest prevalence. Our results suggest that Amphimerus spp. flukes are zoonotic pathogens transmitted by domestic animals living with humans.

Amphimeriasis should be considered an endemic liver fluke infection among residents of this Chachi population in Ecuador. Further studies are needed to determine the complete epidemiology and geographic distribution of infection in this region, as well as in other provinces of Ecuador where freshwater fish is eaten undercooked or where the same tropical ecology is found. For example, the Amazonian region has indigenous groups where other foodborne trematodiasis-like paragonimiasis are endemic (14). Amphimerus spp. flukes infecting domestic and wild animals have been reported from Ecuador’s neighboring countries as well as from Central and North America. The existence of undiscovered foci of human infections is possible.

In 1971, Yamaguti (1) suggested that a parasite previously reported in Ecuador (8) as O. guayaquilensis might in fact be Amphimerus spp. Subsequently, publications referred to this parasite as A. guayaquilensis (5,7); however, the accuracy of this reclassification is unclear. Molecular analysis could help clarify the ambiguities in genus/species identification of O. guayaquilensis and the conspecific species of Amphimerus (15).

We have much to learn about the pathology and epidemiology of Amphimerus spp. flukes. For example, nothing is known about the clinical and pathologic significance of infections with this parasite. Praziquantel eliminated the parasites in these patients, but whether the dose and treatment time were adequate are unknown. Additionally, little is known about epidemiologic factors responsible for the differences in the number of infections among the different population groups. Future studies can help determine the direct and indirect public health implications of this new foodborne zoonosis.

Dr Calvopiña is a professor in the Department of Molecular Parasitology and Tropical Medicine, Centro de Biomedicina, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador. His major research interest is parasitic diseases, including leishmaniasis, paragonimiasis, onchocerciasis, and intestinal parasite infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the community health workers of Borbon and Rio Cayapas, Esmeraldas, for informing study participants, preparing and obtaining the consent, and translating to the local language in the communities surveyed. We also thank Jeyson Abarca for performing duodendoscopy and Ronald Guderian for revising the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health, grant no. RO1-AI050038.

References

- Yamaguti S. Synopsis of the digenetic trematodes of vertebrates. Vols. 1 and II. Tokyo: Keigaku Co; 1971. p. 1074.

- Bowman DD. Amphimerus pseudofelineus (Ward 1901) Barker, 1911. In: Feline clinical parasitology. 1st ed. Ames (IA): Iowa State University Press; 2002. p. 151−53.

- Miyazaki I, Kifune T, Habe S, Uyema N. Reports of Fukuoka University scientific expedition to Peru, 1976. Department of Parisitology, School of Medicine Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan. 1978;1:1–28.

- Rivillas C, Caro F, Carvajal H, Velez I. Algunos trematodos digeneos (Rhopaliasidae, Opistorchiidae) de Phillander Opossum (Marsupialia, mammalia) de la Costa Pacifica Colombiana, Incluyendo Rhopalias caucensis N.SP. 2004 [cited 2011 Oct 20]. http://www.accefyn.org.co/revista/Vol_28/109/14_591_600

- de Moraes Neto AHA, Thatcher VE, Lanfredi RM. Amphimerus bragai N.sp. (Digenea: Opisthorchiidae), a parasite of the rodent Nectomys squamipes (Cricetidae) from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (Rio de Janeiro). 1998;93:181−86.

- Artigas PT, Perez MD. Consideracoes sobre Opisthorchis pricei Foster 1939, O. guayaquilensis Rodriguez, Gomez e Montalvan 1949 e O. pseudofelineus Ward 1901. Descricao de Amphimerus pseudofelineus minumus n. sub. sp. Mem Inst Butantan. 1962;30:157–66.

- Thatcher VE. The genus Amphimerus Barker, 1911. (Trematoda: Opisthorchiidae) in Colombia with the description of a new species. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington. 1970;37:207–11.

- Rodriguez JD, Gomez-Lince LF, El Montalvan JA. Opisthorchis guayaquilensis. Rev Ecuat Hig Med Trop. 1949;6:11–24.

- Moreira J, Gobbo M, Robinson F, Caicedo C, Montalvo G, Anselmi M. Opistorquiasis en Esmeraldas: Hallazgo casual o problema de importancia epidemiológica? Boletin Epidemiologico. 2008;5:24–30.

- Instituto Nacional Ecuatoriano de Censos. VI Censo de población y de vivienda [Sixth census of population and housing]. Quito, Ecuador: Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas y Censo; 2001.

- Eisenberg JN, Cevallos W, Ponce K, Levy K, Bates SJ, Scott JC, Environmental change and infectious disease: how new roads affect the transmission of diarrheal pathogens in rural Ecuador. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19460–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chai JY, Park JH, Han ET, Guk SM, Shin EH, Lin A, Mixed infections with Opisthorchis viverrini and intestinal flukes in residents of Vientiane Municipality and Saravane Province in Laos. J Helminthol. 2005;79:283–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Trostle JA, Hubbard A, Scott J, Cevallos W, Bates SJ, Eisenberg JN. Raising the level of analysis of food-borne outbreaks: food-sharing networks in rural coastal Ecuador. Epidemiology. 2008;19:384–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Calvopiña M, Guderian RH, Paredes W, Cooper PJ. Comparision of two single-day regimens of triclabendazole for the treatment of human pulmonary paragonimiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:451–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Park GM. Genetic comparison of liver flukes, Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini, based on rDNA and mtDNA gene sequences. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:351–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 17, Number 12—December 2011

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|