Volume 30, Number 10—October 2024

Research

Early Introductions of Candida auris Detected by Wastewater Surveillance, Utah, USA, 2022–2023

Abstract

Candida auris is considered a nosocomial pathogen of high concern and is currently spreading across the United States. Infection control measures for C. auris focus mainly on healthcare facilities, yet transmission levels may already be significant in the community before outbreaks are detected in healthcare settings. Wastewater-based epidemiology (culture, quantitative PCR, and whole-genome sequencing) can potentially gauge pathogen transmission in the general population and lead to early detection of C. auris before it is detected in clinical cases. To learn more about the sensitivity and limitations of wastewater-based surveillance, we used wastewater-based methods to detect C. auris in a southern Utah jurisdiction with no known clinical cases before and after the documented transfer of colonized patients from bordering Nevada. Our study illustrates the potential of wastewater-based surveillance for being sufficiently sensitive to detect C. auris transmission during the early stages of introduction into a community.

Candida auris is an antifungal-resistant yeast that leads to high mortality rates among patients with underlying conditions and displays a formidable persistence in healthcare settings because of its biofilm-forming potential and resistance to some commonly used disinfectants (1–3). Circulating strains are classified into 5 genomic clades linked to their geographic area of origin: clade I (southern Asia), clade II (eastern Asia), clade III (Africa), clade IV (South America), and clade V (Iran) (4,5). Since C. auris introduction into the United States was documented in 2013 (6), prevalence has increased rapidly and the organism has become endemic to many jurisdictions (7). The strain exerted by the COVID-19 pandemic on infection control practices and public health resources in general is thought to have contributed to C. auris expansion (8).

Despite the widespread prevalence of C. auris in the United States, its effect on healthcare facilities should be limited, and jurisdictions that have not yet experienced sustained transmission should be protected. In addition to classic infection prevention strategies focused on admission screenings, point prevalence surveys (PPSs), and interfacility communication (9,10), wastewater-based surveillance could help control the spread of emerging pathogens by providing opportunities for early detection and management of outbreak responses (11–13).

We and others have previously shown the feasibility of community-scale wastewater surveillance for C. auris in high disease prevalence settings, specifically Nevada and Florida (14–16). We monitored the influent of the only wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in St. George, Utah, before and after the transfer of a C. auris–positive patient into that community. On the basis of available epidemiologic information and modeling, we propose that wastewater surveillance could be a sufficiently sensitive strategy for early detection of C. auris, before it is detected in clinical surveillance efforts. In addition, we report improvements to the culture method that we originally used to recover C. auris isolates from wastewater and demonstrate the utility of organism isolation in providing high-quality genomic data for investigations. Our study was performed under Utah Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Institutional Review Board protocol no. 651 (“Community and facility level surveillance for multidrug resistant organisms using wastewater samples”).

Wastewater Sample Collection and Transport

During November 2022–June 2023, we collected 24-hour composite influent wastewater samples from 3 WWTPs in southwestern Utah, near the border with Nevada: St. George (population ≈92,000), Ash Creek (≈25,000), and Cedar City (≈32,000) (Table 1; Figure 1, panel A). The St. George WWTP served as the primary experimental site, and the Ash Creek and Cedar City WWTPs served as presumptive negative control sites (Table 1). The average flow rate for the St. George WWTP during this study was 12.73 million gallons per day (mgd), which corresponds to 138 gallons per capita per day (gpcd). The per capita wastewater generation rate is similar to the national average of 132 gpcd (17). Each sample consisted of 250 mL of influent wastewater collected in polypropylene bottles and transported on ice (≈24 hours) to the Utah Public Health Laboratory (UPHL). Subsequently, 150-mL aliquots of each sample were shipped on ice with an overnight priority service (≈24 hours) to the Southern Nevada Water Authority laboratory.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Monitoring and Performance Characteristics

To perform wastewater surveillance of C. auris, the Southern Nevada Water Authority used quantitative PCR (qPCR) as previously described (15). In the earlier study, the statistical limit of quantification was determined to be a quantification cycle (Cq) of 33.03 (15), which equated to an average of 7 gene copies (gc) across all study-specific standard curves, and the theoretical limit of detection was assumed to correspond to 1 gc. Across 18 samples in our study, the average equivalent sample volume (ESV) for each qPCR reaction was 1.07 ± 0.81 mL of influent wastewater, yielding an average limit of detection of 2.97 log10 gc/L. Limits of quantification ranged from 3.95 to 4.47 log10 gc/L based on variability in run-specific standard curves and an assumed average ESV of 1.07 mL (Appendix).

C. auris Isolation by Culture of Filter-Based Concentration

We vacuum filtered <50 mL of influent wastewater through 0.45-μm cellulose nitrate analytical filters (ThermoFisher Scientific, https://www.thermofisher.com). We removed the filters from the vacuum unit by using forceps, placed the filters in a 50-mL conical tube, and submerged them in 12 mL of Salt Sabouraud Dulcitol Broth (2) (Thomas Scientific, https://www.thomassci.com) supplemented with 32 μg/mL fluconazole (14). The submerged filters were incubated at 42°C for up to 5 days with vigorous agitation at 250 rpm. We performed plating of the broth after incubation on chromogenic media and species identification of presumptive colonies as previously described (14).

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics

We sequenced C. auris genomes by using a NextSeq platform (Illumina, https://www.illumina.com). We performed single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) distance analyses by using the MycoSNP pipeline (18), as previously described (14).

Monte Carlo Modeling

We created a model to assess the theoretical sensitivity of the wastewater qPCR method for detecting C. auris from 1 shedding person in the sewershed. The model predicts the concentration of C. auris in wastewater (in gc/L) from 1 shedder (Table 2). We performed a Monte Carlo simulation by using 10,000 random samplings of the parameter distributions to characterize the distribution of possible C. auris concentrations with 1 C. auris shedder contributing urine and feces to the wastewater (Appendix).

Epidemiology Data and Infection Control Practices

C. auris reporting and submission of isolates or residual primary specimens is regulated by the Utah Communicable Disease Rule R386-702. The Utah DHHS uses EpiTrax as the centralized reportable disease database (25). Reports are filed electronically or via manual entry after notification to Utah DHHS by fax. Federal regulations recommend transfer notifications of patients colonized or infected with C. auris; however, compliance is seldom enforced, and effective interfacility communication relies on good infection prevention stewardship.

PPSs were conducted via composite axilla/groin swabbing (26) with nylon swabs, and samples were transported in liquid Amies (Eswab system; Copan, https://www.copanusa.com). We processed 200 μL of Amies media by using the on-board extraction PCR system BDMax (Becton, Dickinson and Company, https://www.bd.com) (27).

Introduction of C. auris into St. George

In November 2022, the Utah DHHS was notified about the upcoming transfer of a patient with an active C. auris infection from Nevada to St. George, Utah (patient 1). Before patient 1 was transferred, no C. auris case or colonized person had been recorded in Utah. On November 10, 2022, patient 1 was transferred from an acute-care hospital (ACH A) in Nevada to a skilled nursing facility (SNF A) in St. George (Figure 1, panels B, C). Patient 1 was highly debilitated and while in St. George had a C. auris–positive urine culture (>105 CFU/mL); the patient died after the transfer (December 2022) (Figure 1, panel C). No additional colonized persons were discovered at SNF A through a PPS evaluating 40 persons.

In March 2023, Utah DHHS was notified about the transfer of a second C. auris–colonized person from Nevada (patient 2). Patient 2 had been hospitalized in a different acute-care hospital in Nevada (ACH B) and was admitted to SNF A in St. George on March 23, 2023; the patient remained there for the duration of our wastewater surveillance study (Figure 1, panels B, C).

We discovered a third patient from Nevada (patient 3) retrospectively. Patient 3 previously resided at ACH B in Nevada (similar to patient 2) but was not found to be colonized with C. auris before being transferred to St. George in December 2022 (Figure 1, panels B, C). Because of the risk factor associated with patient 3 being transferred from a healthcare facility with an ongoing outbreak (i.e., ACH B in Nevada), the acute-care hospital in St. George (ACH C) ordered an admission screening, which led to confirmation of C. auris colonization on December 28, 2022 (Figure 1, panels B, C). The colonization status of patient 3 was communicated via fax to the Utah DHHS according to Utah communicable diseases rules; however, the alert was overlooked because of human error. After 2 days at ACH C, patient 3 was discharged and continued to receive dialysis in an outpatient setting in St. George until June 2023, albeit by commuting between his residence in Nevada and St. George (Figure 1, panel C).

Collectively, the 3 patient transfers potentially resulted in nearly continuous shedding of C. auris into St. George wastewater during November 2022–June 2023, which coincided with the duration of our wastewater surveillance study. Moreover, patients 2 and 3 simultaneously resided or spent a substantial amount of time in St. George during March–June 2023 (Figure 1, panel C), potentially increasing C. auris loading in local wastewater.

Detection of C. auris in St. George Wastewater

After being notified of the pending transfer of patient 1 to St. George, we identified a unique opportunity to assess the sensitivity of wastewater surveillance for the early detection of C. auris. On November 8, 2022 (2 days before the transfer), we initiated qPCR-based wastewater surveillance at the St. George WWTP (Figure 1, panel C), which continued at irregular intervals until June 13, 2023 (Table 1; Figure 1, panel C). C. auris was not detected (i.e., below the limit of detection) in the first 2 samples collected for the study (November 8 and 15), which straddled the transfer date of patient 1 (Table 1; Figure 1, panel C). However, C. auris was detected, albeit below the limit of quantification, in a sample collected on November 29 and was detected in every sample thereafter (Table 1; Figure 1, panel C). Before March 2023, only 2 of 7 samples were above the limit of quantification, but starting in April 2023, when patients 2 and 3 were potentially contributing to the St. George WWTP, all samples were above the limit of quantification (Table 1; Figure 1, panel C).

To assess potential transmission in areas near St. George, we also analyzed 4 influent wastewater samples from WWTPs in Ash Creek and Cedar City (Figure 1, panel A). C. auris was not detected in those presumptive negative control samples (Table 1).

Modeled Sensitivity of qPCR-based, Community-Scale Wastewater Surveillance

Given the available epidemiologic data and the fact that C. auris was not detected in the sample collected before the initial transfer of patient 1, the subsequent C. auris–positive wastewater could represent detection of its initial introduction in St. George. If true, that finding indicates that qPCR-based wastewater surveillance may be sufficiently sensitive to detect a single C. auris shedder in a sewershed serving ≈100,000 inhabitants.

To gauge the plausibility of that statement, we used a Monte Carlo simulation model previously used for SARS-CoV-2 but adapted to C. auris (28). The model considers the following parameters: C. auris concentration ranges for urine and feces (based on a neutropenic mouse model and quantitative analyses of urine clinical cultures [19,22]); urine and feces production rates in healthy humans (20,21,23); variable gc numbers of the qPCR target (internal transcribed spacer 2) across C. auris strains (based on a nucleotide BLAST analysis in which the sequence of the qPCR probe was searched in various C. auris genomes, as well as the number of rRNA genes reported in C. albicans as an upper hypothetical value [24,29,30]); and average daily wastewater flow rate (Table 2).

The primary site of C. auris colonization is skin (31), and routine hygiene practices (e.g., handwashing, showering, laundering) should also represent a major route for release of organisms into the sewer system. However, we did not incorporate that shedding mode in our model because it would entail assumptions with considerable uncertainty (e.g., affected water volumes, affected skin surface area, skin mobilization rate, frequency of handwashing/showering/laundering).

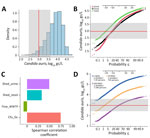

Our model indicates that 97% of the predicted C. auris wastewater concentrations resulting from 1 person shedding the pathogen in urine and feces were above the average limit of detection for our study (2.97 log10 gc/L; assumes a limit of 1 gc and the average of all sample-specific ESVs for our study) (Figure 2, panels A, B). The median predicted concentration from the Monte Carlo simulation was 3.90 log10 gc/L, a value greater than the upper limit of observed limits of detection (i.e., 3.60 log10 gc/L; assumes a limit of 1 gc and the average of all sample-specific ESVs for our study) (Figure 2, panel A). The upper-bound probability of detection increases to 99.9% when the lowest limit of detection is considered (Figure 2, panel B). If shedding is modeled through either urine or feces alone, the probability of detection decreases to ≈85% when the average limit of detection is considered (Figure 2, panel B).

To determine the effect of each stochastic parameter on the final predicted wastewater concentrations, we used the Spearman correlation coefficient to perform a sensitivity analysis on the Monte Carlo model (28) (Figure 2, panel C). The parameter with the strongest correlation was the number of genome copies per CFU, followed by the rate of C. auris shedding in urine (and to a slightly lesser extent, feces). The flow rate had a moderate negative correlation, indicating that an increased flow rate results in a decreased probability of detection in wastewater from 1 shedder. To better illustrate this effect, we generated probability plots for 3 hypothetical WWTP flow rates: 1, 10, and 100 mgd. Assuming the St. George per capita wastewater generation rate of 138 gpcd, those flow rates represent C. auris infection prevalences of 1 in 7,200 (flow rate 1 mgd), 1 in 72,000 (flow rate 10 mgd), and 1 in 720,000 (flow rate 100 mgd) persons. At the average limit of detection, the detection probability relative to a single shedder was almost 100% at a flow rate of 1 mgd, ≈97.5% at 10 mgd, and 50% at 100 mgd (Figure 2, panel D). Altogether, our modeled and observed results support the hypothesis that use of qPCR-based wastewater surveillance for C. auris can achieve sensitivity on the order of 1 in 100,000.

Isolation of C. auris from the St. George Sewershed and Genetic Relatedness to Clinical Isolates

We complemented qPCR-based wastewater surveillance with culturing and subsequent whole-gene sequencing of recovered isolates. Initial attempts with the centrifugation-based method previously used for southern Nevada wastewater (14) were unsuccessful (Table 1). As such, we explored a filtration-based alternative that was observed to be superior to our original method across 2 split samples from Nevada (Appendix Figure 1). Using that improved method, we were able to recover 15 C. auris isolates from 2 samples consecutively collected on March 28, 2023, and April 4, 2023 (Table 1). All wastewater isolates belonged to clade III and segregated topologically into 2 individual subgroups distinctly separated by collection date (Figure 3). Isolates within the subgroup linked to the March 28 wastewater sample were highly related to the clinical isolate available for patient 2 (0–6 SNPs), who was transferred to St. George on March 23. The isolates within the subgroup linked to the April 4 sample displayed ≈12 SNP differences from the patient 2 isolate (Figure 3). Unfortunately, no clinical whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data were available for patient 3 because the patient’s colonization status was not determined in Nevada and the positive clinical sample collected in Utah was not submitted to UPHL. Patient 1 was infected with a clade I strain, but we were unable to culture C. auris in any wastewater samples collected during the time of the patient’s stay at SNF A or before March 28, 2023 (Table 1). As such, we were unable to study the contribution of clade I isolates to the overall C. auris signal in the St. George sewershed.

The recent history of C. auris in the United States highlighted the challenges in controlling the pathogen after it becomes established in an area (7). Early detection strategies coupled with aggressive infection control measures could reduce its effect on healthcare facilities and the general population. In that respect, wastewater-based surveillance is a promising tool for detecting pathogens that are circulating in the population at very low prevalence and have not been overtly manifested at the clinical level (12).

The application of wastewater-based surveillance to the C. auris problem is in its infancy (14–16), so fundamental parameters that will guide its use have not yet been studied in detail. For example, levels of C. auris shedding in human excreta and body site densities during colonization have not yet been adequately characterized. C. auris effectively colonizes skin and nares (26,31) but is not typically recovered from the buccal mucosa (31,32). A regular nylon swab can usually recover 102–1010 CFU of C. auris from various skin sites (e.g., palms/fingertips, toe web, perianal skin, axilla, inguinal crease, neck) and nares (31). As such, it is conceivable that the organism could be released in great numbers into the sewershed via skin shedding during routine hygiene practices or even when laundering items that have been in contact with a colonized person. Because skin is the primary C. auris colonization site, clinical studies aimed at determining the actual bioburden released through hygiene practices (33) will be essential for assessing quantitative measurements in wastewater. C. auris is also commonly recovered from urine (4,26) of patients with candiduria (34), as well as from asymptomatic persons (35). C. auris is less frequently recovered from fecal samples but has been recovered via rectal swabbing (26,32,36). Of note, a correlation between gut colonization and urinary tract infections has been observed in cohorts of patients affected by C. auris (36).

As has been accomplished for wastewater-based surveillance of SARS-CoV-2, additional modeling and parameterization are needed to fully characterize relationships between incidence/prevalence and expected wastewater concentrations (28,37). Early attempts to establish those correlations for C. auris have been extremely challenging (16). Nevertheless, the qPCR data and the excreta-only model used in our study fit very well with the clinical course of patient 1 (the putative introduction event in St. George) and indicate that detecting 1 C. auris shedder to a community-scale wastewater system of moderate size is plausible (Figure 2). Although our study focused on early detection of pathogen introduction, future studies should consider monitoring wastewater C. auris loads after the population presumably returns to a zero-infection status.

Recovery of C. auris in culture has been instrumental in obtaining isolates for molecular epidemiology analyses by WGS (14). The incorporation of WGS into wastewater-based surveillance systems for C. auris should be universally adopted to understand the origin of introduction events as well as the evolving diversity of contributions to sewersheds. Motivated by the initial inability to recover C. auris isolates in St. George (Table 1), we worked at improving our original culture method by changing the sample concentration step from centrifugation to membrane filtration (Appendix Figure 1), an approach also recently used by Babler et al. (16). Yet, culture from wastewater samples remains a highly variable endeavor, possibly because of variable competition from other species of fungi or fluctuations in environmental factors within the sewer environment affecting the growth of C. auris, such as dissolved oxygen concentration (38,39). In addition, our broth enrichment approach remains unsuitable for isolating fluconazole-susceptible isolates (14).

WGS analysis indicated a close relationship between C. auris wastewater isolates and 1 isolate from patient 2 (Figure 3). When those wastewater samples were collected, both patients 2 and 3 were potentially contributing C. auris to the St. George WWTP (Figure 1, panel C). With the data available, we cannot discriminate whether the genetic diversity of the wastewater isolates collected on 2 separate dates encompasses shedding from patient 3 or other unidentified colonized persons. Moreover, mixed colonization consisting of clones separated by SNP distances greater than those displayed in Figure 3 is not unusual (40,41) and represents another layer of complexity in the interpretation of molecular epidemiology analyses for C. auris (42). However, incorporating WGS analyses into C. auris wastewater surveillance would still be invaluable for detecting contributions from strains belonging to different clades or displaying very large SNP distances. In addition, if C. auris strains can persist in sewer pipes as biofilm (a phenomenon not yet investigated for this organism) (38), WGS could potentially distinguish persistent signals from a new shedding event.

In conclusion, we used a holistic approach to C. auris wastewater-based surveillance that entailed using qPCR as the main testing method, as well as culture and WGS to better characterize the source of the molecular signals. After being proven effective, metagenomic approaches could potentially bypass the need for culture (43). We believe that our case study illustrates the potential of wastewater-based surveillance to be a sufficiently sensitive method for discovering C. auris transmission at early stages of introduction into a community.

Mr. Chavez is an ORISE (Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education) Fellow at CDC. His research expertise encompasses environmental microbiology, wastewater surveillance, and mycotic diseases. Dr. Crank is a research microbiologist at the Southern Nevada Water Authority. Her research expertise encompasses environmental health engineering, environmental microbiology, and wastewater surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Gorzalski for sharing clinical isolates sequences. We are grateful for the support and contributions of many groups: the Healthcare-associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance team at Utah DHHS and the Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network, NGS, and wastewater testing teams at UPHL.

J.C. was supported by an Association of Public Health Laboratories Fellowship in Antibiotic Resistance (cooperative agreement no. NU60OE000104, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] through the Association of Public Health Laboratories). Southern Nevada wastewater sample collection was supported by CDC grant NH75OT000057-01-00.

References

- Lone SA, Ahmad A. Candida auris-the growing menace to global health. Mycoses. 2019;62:620–37. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Welsh RM, Bentz ML, Shams A, Houston H, Lyons A, Rose LJ, et al. Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic health care surface. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2996–3005. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ku TSN, Walraven CJ, Lee SA. Candida auris: disinfectants and implications for infection control. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:726. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, Farooqi J, Chowdhary A, Govender NP, et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:134–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chow NA, de Groot T, Badali H, Abastabar M, Chiller TM, Meis JF. Potential fifth clade of Candida auris, Iran, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1780–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vallabhaneni S, Kallen A, Tsay S, Chow N, Welsh R, Kerins J, et al.; MSD. MSD. Investigation of the first seven reported cases of Candida auris, a globally emerging invasive, multidrug-resistant fungus—United States, May 2013–August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1234–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lyman M, Forsberg K, Sexton DJ, Chow NA, Lockhart SR, Jackson BR, et al. Worsening spread of Candida auris in the United States, 2019 to 2021. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176:489–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Thoma R, Seneghini M, Seiffert SN, Vuichard Gysin D, Scanferla G, Haller S, et al. The challenge of preventing and containing outbreaks of multidrug-resistant organisms and Candida auris during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: report of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak and a systematic review of the literature. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11:12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saleem Z, Godman B, Hassali MA, Hashmi FK, Azhar F, Rehman IU. Point prevalence surveys of health-care-associated infections: a systematic review. Pathog Glob Health. 2019;113:191–205. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang TZ, White KN, Scarr JV, Simon MS, Calfee DP. Preparing your healthcare facility for the new fungus among us: An infection preventionist’s guide to Candida auris. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:825–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vo V, Tillett RL, Papp K, Shen S, Gu R, Gorzalski A, et al. Use of wastewater surveillance for early detection of Alpha and Epsilon SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and estimation of overall COVID-19 infection burden. Sci Total Environ. 2022;835:

155410 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Gupta P, Liao S, Ezekiel M, Novak N, Rossi A, LaCross N, et al. Wastewater genomic surveillance captures early detection of omicron in Utah. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11:

e0039123 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Ryerson AB, Lang D, Alazawi MA, Neyra M, Hill DT, St George K, et al.; 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team. 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team. Wastewater testing and detection of poliovirus type 2 genetically linked to virus isolated from a paralytic polio case—New York, March 9–October 11, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1418–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rossi A, Chavez J, Iverson T, Hergert J, Oakeson K, LaCross N, et al. Candida auris discovery through community wastewater surveillance during healthcare outbreak, Nevada, USA, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:422–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barber C, Crank K, Papp K, Innes GK, Schmitz BW, Chavez J, et al. Community-scale wastewater surveillance of Candida auris during an ongoing outbreak in southern Nevada. Environ Sci Technol. 2023;57:1755–63. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Babler K, Sharkey M, Arenas S, Amirali A, Beaver C, Comerford S, et al. Detection of the clinically persistent, pathogenic yeast spp. Candida auris from hospital and municipal wastewater in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Sci Total Environ. 2023;898:

165459 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Chini CMS, Stillwell AS. The state of U.S. urban water: data and the energy-water nexus. Water Resour Res. 2018;54:1796–811. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Bagal UR, Phan J, Welsh RM, Misas E, Wagner D, Gade L, et al. MycoSNP: A portable workflow for performing whole-genome sequencing analysis of Candida auris. Methods Mol Biol. 2022;2517:215–28. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Torres SR, Pichowicz A, Torres-Velez F, Song R, Singh N, Lasek-Nesselquist E, et al. Impact of Candida auris infection in a neutropenic murine model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01625–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rose C, Parker A, Jefferson B, Cartmell E. The characterization of feces and urine: a review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2015;45:1827–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Penn R, Ward BJ, Strande L, Maurer M. Review of synthetic human faeces and faecal sludge for sanitation and wastewater research. Water Res. 2018;132:222–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Croxatto A, Dijkstra K, Prod’hom G, Greub G. Comparison of inoculation with the InoqulA and WASP automated systems with manual inoculation. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2298–307. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rauch W, Brockmann D, Peters I, Larsen TA, Gujer W. Combining urine separation with waste design: an analysis using a stochastic model for urine production. Water Res. 2003;37:681–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, Dungan J, Kalman S, Magee BB, et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7329–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Whipple A, Jackson J, Ridderhoff J, Nakashima AK. Piloting electronic case reporting for improved surveillance of sexually transmitted diseases in Utah. Online J Public Health Inform. 2019;11:

e7 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Zhu Y, O’Brien B, Leach L, Clarke A, Bates M, Adams E, et al. Laboratory analysis of an outbreak of Candida auris in New York from 2016 to 2018: impact and lessons learned. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01503–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leach L, Russell A, Zhu Y, Chaturvedi S, Chaturvedi V. A rapid and automated sample-to-result Candida auris real-time PCR assay for high-throughput testing of surveillance samples with the BD Max Open System. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e00630–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Crank K, Chen W, Bivins A, Lowry S, Bibby K. Contribution of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding routes to RNA loads in wastewater. Sci Total Environ. 2022;806:

150376 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leach L, Zhu Y, Chaturvedi S. Development and validation of a real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of Candida auris from surveillance samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e01223–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Proctor DM, Dangana T, Sexton DJ, Fukuda C, Yelin RD, Stanley M, et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Integrated genomic, epidemiologic investigation of Candida auris skin colonization in a skilled nursing facility. Nat Med. 2021;27:1401–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Du H, Bing J, Hu T, Ennis CL, Nobile CJ, Huang G. Candida auris: Epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:

e1008921 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Plano LR, Garza AC, Shibata T, Elmir SM, Kish J, Sinigalliano CD, et al. Shedding of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from adult and pediatric bathers in marine waters. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Griffith N, Danziger L. Candida auris urinary tract infections and possible treatment. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9:898. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sayeed MA, Farooqi J, Jabeen K, Awan S, Mahmood SF. Clinical spectrum and factors impacting outcome of Candida auris: a single center study from Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:384. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Piatti G, Sartini M, Cusato C, Schito AM. Colonization by Candida auris in critically ill patients: role of cutaneous and rectal localization during an outbreak. J Hosp Infect. 2022;120:85–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gerrity D, Papp K, Stoker M, Sims A, Frehner W. Early-pandemic wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Southern Nevada: Methodology, occurrence, and incidence/prevalence considerations. Water Res X. 2021;10:

100086 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - McLellan SL, Roguet A. The unexpected habitat in sewer pipes for the propagation of microbial communities and their imprint on urban waters. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2019;57:34–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Day AM, McNiff MM, da Silva Dantas A, Gow NAR, Quinn J. Hog1 regulates stress tolerance and virulence in the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. mSphere. 2018;3:e00506–18. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eyre DW, Sheppard AE, Madder H, Moir I, Moroney R, Quan TP, et al. A Candida auris outbreak and its control in an intensive care setting. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1322–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Roberts SC, Zembower TR, Ozer EA, Qi C. Genetic evaluation of nosocomial Candida auris transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59:e02252–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chow NA, Gade L, Tsay SV, Forsberg K, Greenko JA, Southwick KL, et al.; US Candida auris Investigation Team. Multiple introductions and subsequent transmission of multidrug-resistant Candida auris in the USA: a molecular epidemiological survey. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1377–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huang X, Welsh RM, Deming C, Proctor DM, Thomas PJ, Gussin GM, et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Skin metagenomic sequence analysis of early Candida auris outbreaks in U.S. nursing homes. mSphere. 2021;6:

e0028721 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: September 17, 2024

1These first authors contributed equally to this article.

2Current affiliation: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

3Current affiliation: North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Wilmington, North Carolina, USA.

Table of Contents – Volume 30, Number 10—October 2024

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Alessandro Rossi, Utah Public Health Laboratory, 4431 S 2700 West, Taylorsville, UT 84129, USA

Top